|

Albert Namatjira showed his paintings

for the first time when Pastor Albrecht exhibited ten

of them in Nuriootpa in the Barossa Valley. In 1938 Namatjira

led Battarbee to Ilypilli Waterhole - or llypilli Springs,

as it was then known. Albrecht had established a mission

outpost there to make contact with the remote Pintubi

people, and Titus, a relative of Namatjira's, had remained

there as the evangelist. At this time Ilypilli was the

canter of the known world for Pintubi people. A large

and permanent waterhole, it serviced an extensive region

of the desert for the Pintubi and a large number of their

Warlpiri neighbours.

Although the Pintubi ranged widely into

Western Australia on their traditional country, as rain

became less frequent they retreated to more permanent

supplies, eventually collecting at Ilypilli in times of

drought. It was therefore an important place to make contact,

and it was here where the Pintubi gathered in the second

wave of contact that resulted in the Pintubi settlement

at Papunya in the

1960s. These Pintubi were to form the backbone of the

present acrylic painting movement among desert peoples.

Commercial Success

Namatjira's first Adelaide exhibition

was held at the Royal South Australian Society of Arts

in November 1939. A painting from this exhibition was

sold to the Art Gallery of South Australia, but the work

did not find easy acceptance in fine-art circles. Although

watercolour painting was popular in the 1950s, it was

a time when Australian art in general had moved on. In

1954 the National Gallery of Victoria rejected a recommendation

to purchase one of Albert Namatjira's pictures, and it

was to be many years before he achieved his full standing

as a major Australian artist.

As tourism to the Centre increased, Namatjira

was able to earn a significant living for himself and

his family. The taxis that took him to and from Hermannsburg

sent signals to other families that art was a route to

status and economic independence.

|

Many others took up watercolour

painting. These were mostly relatives of Albert

Namatjira and included his sons Enos, Oscar, Ewald,

Maurice and Keith.

Otto Pareroultja and his brothers

Ruben and Edwin were very significant artists, as

was Walter Ebatarinja. This first wave of Aranda

artists were all male, their principal teachers

being Namatjira himself and Rex Battarbee, who took

up permanent residence at Hermannsburg during the

Second World War and later moved to Alice Springs. |

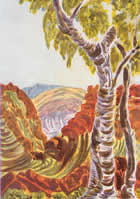

Gum Tree and Gorge,

James Range

Gum Tree and Gorge,

James Range

by Otto Pareroultja |

Politics intervened during the war. The

Federal Government placed Battarbee in charge of the community

in an attempt to control German influence. Gayle Battarbee

points out that it was only after the war ended, and her

father had married, that women began to paint. The first

of these women artists were Cordula Ebatarinja and Gloria

Moketarinja.

Namatjira continued to paint throughout

his life. By 1955 he was nationally famous, and feted

in Sydney. After a trip there he returned to the Centre

exhausted and perhaps marginalised by the social set he

had met. This is a situation many Aboriginal people experience

today. In the highly charged atmosphere of the contemporary

art movement, they are occasionally treated as oddities;

their work is valued but to some art patrons the people

themselves remain strange, alien and 'other'.

Development

of the Aranda Watercolour Artists

Battarbee opened a gallery in Alice Springs

in 1951. He continued to advise artists by commenting

on the technical aspects of the work that they brought

to sell him, and by showing them art books. He favoured

the impressionists, especially Cezanne, Monet and Van

Gogh (particularly his trees), and the work of Picasso.

Battarbee advised on clean washes, mixing paints and how

to organise a composition. He often commented on what

he called the temperature of a colour in order to achieve

perspective and aesthetics.

He was fond of placing a gum tree on

the left of his own pictures, and possibly set a trend

which continues to the present day. He encouraged the

artists to put red in the foreground of the picture and

blue at the back (until very recently the hills were always

blue). It is interesting to compare this principle with

the current practice of the Hermannsburg Potters. They

often reverse this colour layering to unusual effect,

creating unexpected visual sensations. The artist may

have pink ranges, for example, but also continue to employ

features or elements of composition that are derived from

the painting movement - rolling hills, rows of acacias

and dotted herbage.

Paintings by Otto Pareroultja were prolific

and much admired by Battarbee, who saw in them design

elements of linear patterns parallel lines and circles

from traditional symbolic arc. In the 1950s and 1960s

at Hermannsburg, artists would occasionally pay a debt

by adjusting traditional customs of exchange to incorporate

art practice. So, according to Gayle Griffiths, Albert

Namatjira taught and encouraged other relatives such as

Walter Ebatarinja. Albert might do the hills and the gum

tree and, under supervision, Walter would finish the background.

Albert would sign the painting, thereby giving a 'gift'

to Walter of his teaching and the finished work his imprimatur.

This was offered as the dutiful and generous response

to kinship obligations towards Walter's father.

The custom of artists occasionally working

on sections of each other's paintings - particularly as

Albert taught so many people the skills - points to the

fact that cooperation is central to the successful outcome

of any craft venture. It is this cooperative approach

to learning and art creation that continues among the

potters of today, in some ways similar to the Renaissance

artisan guilds of Europe.

Albert Namatjira was made a full Australian

citizen in 1957. The Australian Government considered

this a singular honour, not bestowed on any other Aboriginal

person at that time. He was entitled to live in Alice

Springs and occasionally to purchase a bottle of alcohol.

However, Namatjira's relations, including

his children, were not permitted the same privileges.

Aranda social custom was that personal property could

not exist - everyone shared what they had. Thus, in 1958,

in a brawl in which a woman was killed by her husband,

some people felt that Namatjira was responsible because

it was through his citizenship that alcohol had entered

the community. He had left liquor in the camp, someone

else had found it, and he was charged with supplying alcohol.

Sentenced to six months' labour, Albert

Namatjira served two months in the government prison at

Papunya but, on release, died in Alice Springs hospital

in 1959.

|